It’s 63C (145F) deep inside Borosil Renewables Ltd.’s vast manufacturing site in Bharuch, western India, where 1,000 tons of molten glass a day is pressed through glowing furnaces into flawless, paper-thin sheets that will eventually form solar panels.

Three female staff stationed on a gantry above one of the sweltering manufacturing lines peer down to scan for the smallest of imperfections, using a long wooden stick topped with an ink-soaked cloth to mark any defects. The workers are an additional layer of defense, adding to checks being made remotely through a bank of cameras.

“We make specialized glass, there's absolutely no room for error,'' said Pradeep Kumar Kheruka, the producer’s executive chairman. His company has seen output jump more than five-fold since 2010, adding a focus on renewable energy to the parent firm’s decades of expertise in consumer and laboratory glassware.

India’s economic growth and rapidly accelerating electricity consumption are helping to propel a local solar industry that’s forecast to become second in size only to China by the mid-2030s, according to BloombergNEF. That dramatic expansion offers one of the most enticing opportunities in the energy sector — a chance to supply abundant domestic demand for clean power, and to build sufficient scale to compete in export markets with currently dominant Chinese suppliers.

It’s a prospect that’s fueling the growth ambitions of Borosil and competitors across the supply chain, from incumbent energy giants like billionaire Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries Ltd. and Tata Power Co. to specialist producers Waaree Energies Ltd. and Premier Energies Ltd., both among India’s wave of recent green technology listings.

“Opportunities for India are massive,’’ said Vinay Rustagi, chief business officer at Hyderabad, India-based Premier Energies. “Many countries are trying to reduce their imports from China and when they do that, India is the most attractive place.”

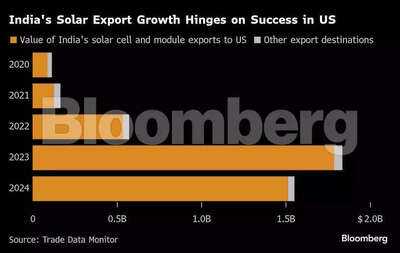

Yet to take advantage of the nation’s potential, India’s solar champions face two major hurdles. Not only do they need to overcome trading tensions with the US that threaten to curb sales to the country’s top export market, but the companies must also expand domestic manufacturing capacity while simultaneously limiting reliance on China for raw materials, equipment and expertise.

US tariffs on India’s solar exports will likely rise to 64% by the end of this month and risks pricing manufacturers “out of their largest and most lucrative overseas market,” BNEF analysts including Rohit Gadre said in an Aug. 12 report.

“Many in the industry had felt that the US would pursue a 'friendshoring' approach that would benefit India, these US tariffs are a sharp departure,” Gadre said in an interview. Equally, heavy reliance on component imports from China “is a big risk for domestic manufacturers,” he said.

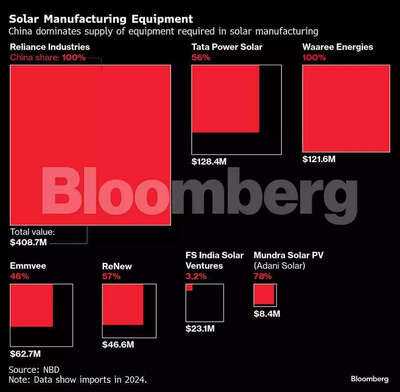

An analysis of trade data by Bloomberg News shows just how difficult a reordering of supply chains could prove. China remains the dominant supplier of almost every item required — including specialized glass, encapsulant film, crystalline silicon wafers and copper ribbon, to fully finished solar cells, and the modules that cluster those cells together.

For solar glass and aluminum frames, four of India’s main panel producers were each more than 97% dependent on Chinese imports in 2024, while only 2 of 7 leading firms sourced more than half of their manufacturing equipment outside China.

Last year, two Chinese companies accounted for more than half of all manufacturing machinery purchases by India’s 10 largest solar importers. Reliance alone spent roughly $300 million sourcing equipment for a giant plant in Gujarat with a single supplier — Suzhou Maxwell Technologies Co., the trade data show. Jiangsu-province based Suzhou declined to comment, Reliance didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Waaree works “with a variety of global suppliers to meet immediate needs, while we continue to strengthen our domestic manufacturing capabilities,” Chief Executive Officer Amit Paithankar said. FS India Solar’s parent company First Solar Inc. declined to comment. Adani Group’s Mundra Solar Energy Ltd., Tata Power and Emmvee Photovoltaic Power didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

While progress is being made on localizing the solar supply chain, ReNew Energy Global Plc has slowed plans to invest in solar wafer-making capacity because of a lack of local availability of specialist machinery, Chief Financial Officer Kailash Vaswani said.

India’s success in onshoring more of the supply chain will determine exactly how much the nation can benefit from global solar investment through 2050. That could total $4.8 trillion if the world sticks with economics-led policies, and as much as $6.9 trillion under more aggressive decarbonization efforts to hit net zero by 2050, according to BNEF estimates.

There’s potential for India to add significant numbers of additional jobs in the solar industry, which already employs more than 300,000 people, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency. Development of the sector will also help to drive down the costs of the nation’s electricity, said Rishabh Jain, senior program lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, a New Delhi-based think tank.

“Our priority should be to reduce our dependency on China,” CEEW’s Jain said. “There is room even for India to raise its ambition for clean energy deployment.”

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government – which aims to have 500 gigawatts of clean energy capacity by 2030, roughly double the current total — has had some, albeit limited, impact with policies aimed at stimulating the domestic solar sector. A total of 22 gigawatts of new renewables capacity was added in the first half of 2025, a record volume and 56% more than a year earlier, according to the Central Electricity Authority.

Import duties of 40% on solar modules and 25% on solar cells were imposed in 2022. Project developers must also use modules supplied only by a government-approved list of manufacturers. While India’s module imports totaled about 20 gigawatts in 2024 — 85% of which were from China — the total plunged after the rule was brought back into force last April, following a year of relaxation to ease a module supply crunch.

Module production has grown twelve-fold since early 2021 and solar cell manufacturing capacity more than doubled in the past year, government data shows.

A crucial next task is to ensure India is producing sufficient quantities of solar cells — which would enable local firms to assemble more finished modules and panels. An approved cell supplier list is scheduled to kick in from June 2026, though that deadline could be dependent on the continued rapid expansion of local plants and the ability of domestic producers to lower costs.

For now, China-made modules remain cheaper than domestic products even after a 40% import tax is applied, though costs of India-made equipment fell almost a third last year and are expected to continue to decline as the local industry builds scale.

The US is India’s dominant export market, and was the destination for 97% of module shipments in the first half. India’s manufacturers have had ambitions of rapidly lifting those volumes, and capitalizing on US wariness about China’s dominance of clean technology.

Yet the strategy faces a fresh challenge from President Donald Trump’s trade policies. Trump on Aug. 6 threatened to double tariffs on India to 50% by next week as a result of the nation’s purchases of Russian oil, and when combined with an existing 14% levy on solar imports it will mean manufacturers face more punitive terms than some rivals.

US solar companies too, are raising objections to the prospect of increased flows of India-made products. The Alliance for American Solar Manufacturing and Trade, which includes First Solar, Mission Solar Energy and Qcells, in July filed trade petitions against India, Indonesia and Laos, alleging illegal practices by largely Chinese-owned companies operating in those countries. The group has called for antidumping duties of 213.96% to be imposed on India.

The US Department of Commerce — which in April set new duties as high as 3,521% on solar imports from four Southeast Asian countries — has launched an investigation. While there is likely to be a short-term negative hit, “we are hopeful that over a period of time these markets will remain open to us,” Premier Energies’ Rustagi said. “India is in a strong position to supply solar panels and other clean tech equipment to the US and other markets.”

An additional barrier for solar firms outside China has been the No. 2 economy’s grip on supply of manufacturing equipment, and particularly the appliances used at vital stages of the production process. That’s creating further risks for Indian producers, with China already showing a willingness to restrict the flows of some specialized appliances or expertise in competitive sectors.

“They're not sharing that right now with the rest of the world,” ReNew’s Vaswani said. “They would like to obviously retain that part of the value within the country.”

Apple Inc.’s main assembly partner Foxconn Technology Group has faced curbs on equipment imports to India, amid a wider drive by authorities in Beijing to curb technology transfers and to prevent the development of rival supply chains overseas, people familiar with the matter said earlier this year. In July, Foxconn asked hundreds of Chinese engineers and technicians to return home from its iPhone factories in India, according to people with knowledge of the details.

Talks this week in New Delhi between Modi and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, along with the Indian leader’s pending visit to China, have raised some expectations for a thawing of restrictions.

India is gradually building up capacity across the solar supply chain, and will continue to add import restrictions and other measures to foster local manufacturing — potentially including domestic manufacturing requirements for solar projects, according to government officials, who requested anonymity to discuss private policy plans.

In February, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman outlined a broader national manufacturing mission with an aim to bolster India’s export competitiveness. While fine details of the policies are still being developed, solar equipment is being considered among potential priorities, some of the officials said. India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

“Every country has to decide their path for energy security and India has clarity on that, it is taking steps to become self-reliant,” Waaree’s Paithankar said in an interview.

Investors too are showing increasing enthusiasm over India’s green prospects. Solar projects attracted a record $14.2 billion of investment in India last year, according to data complied by BNEF. Waaree, Premier Energies and Acme Solar Holdings Ltd. were among firms that led a flurry of clean energy-related initial public offerings in 2024, while Rayzon Solar, Juniper Green Energy and Emmvee have all filed documents to prepare for a new raft of listings.

At Borosil’s plant in Bharuch, Kheruka explains the facility uses mainly equipment from Europe, though crucial glass tempering machinery was imported from China. The company in May confirmed plans to add 600 tons a day of additional capacity.

The producer has pressed India’s government to continue to support the development of local supply chains and insists greater self-sufficiency in the solar sector is an achievable goal.

“We're making satellites — this is nothing, it's not rocket science,” Kheruka said. “China has absolutely nothing that's unique to them.”

Three female staff stationed on a gantry above one of the sweltering manufacturing lines peer down to scan for the smallest of imperfections, using a long wooden stick topped with an ink-soaked cloth to mark any defects. The workers are an additional layer of defense, adding to checks being made remotely through a bank of cameras.

“We make specialized glass, there's absolutely no room for error,'' said Pradeep Kumar Kheruka, the producer’s executive chairman. His company has seen output jump more than five-fold since 2010, adding a focus on renewable energy to the parent firm’s decades of expertise in consumer and laboratory glassware.

India’s economic growth and rapidly accelerating electricity consumption are helping to propel a local solar industry that’s forecast to become second in size only to China by the mid-2030s, according to BloombergNEF. That dramatic expansion offers one of the most enticing opportunities in the energy sector — a chance to supply abundant domestic demand for clean power, and to build sufficient scale to compete in export markets with currently dominant Chinese suppliers.

It’s a prospect that’s fueling the growth ambitions of Borosil and competitors across the supply chain, from incumbent energy giants like billionaire Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries Ltd. and Tata Power Co. to specialist producers Waaree Energies Ltd. and Premier Energies Ltd., both among India’s wave of recent green technology listings.

“Opportunities for India are massive,’’ said Vinay Rustagi, chief business officer at Hyderabad, India-based Premier Energies. “Many countries are trying to reduce their imports from China and when they do that, India is the most attractive place.”

Yet to take advantage of the nation’s potential, India’s solar champions face two major hurdles. Not only do they need to overcome trading tensions with the US that threaten to curb sales to the country’s top export market, but the companies must also expand domestic manufacturing capacity while simultaneously limiting reliance on China for raw materials, equipment and expertise.

US tariffs on India’s solar exports will likely rise to 64% by the end of this month and risks pricing manufacturers “out of their largest and most lucrative overseas market,” BNEF analysts including Rohit Gadre said in an Aug. 12 report.

“Many in the industry had felt that the US would pursue a 'friendshoring' approach that would benefit India, these US tariffs are a sharp departure,” Gadre said in an interview. Equally, heavy reliance on component imports from China “is a big risk for domestic manufacturers,” he said.

An analysis of trade data by Bloomberg News shows just how difficult a reordering of supply chains could prove. China remains the dominant supplier of almost every item required — including specialized glass, encapsulant film, crystalline silicon wafers and copper ribbon, to fully finished solar cells, and the modules that cluster those cells together.

For solar glass and aluminum frames, four of India’s main panel producers were each more than 97% dependent on Chinese imports in 2024, while only 2 of 7 leading firms sourced more than half of their manufacturing equipment outside China.

Last year, two Chinese companies accounted for more than half of all manufacturing machinery purchases by India’s 10 largest solar importers. Reliance alone spent roughly $300 million sourcing equipment for a giant plant in Gujarat with a single supplier — Suzhou Maxwell Technologies Co., the trade data show. Jiangsu-province based Suzhou declined to comment, Reliance didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Waaree works “with a variety of global suppliers to meet immediate needs, while we continue to strengthen our domestic manufacturing capabilities,” Chief Executive Officer Amit Paithankar said. FS India Solar’s parent company First Solar Inc. declined to comment. Adani Group’s Mundra Solar Energy Ltd., Tata Power and Emmvee Photovoltaic Power didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

While progress is being made on localizing the solar supply chain, ReNew Energy Global Plc has slowed plans to invest in solar wafer-making capacity because of a lack of local availability of specialist machinery, Chief Financial Officer Kailash Vaswani said.

India’s success in onshoring more of the supply chain will determine exactly how much the nation can benefit from global solar investment through 2050. That could total $4.8 trillion if the world sticks with economics-led policies, and as much as $6.9 trillion under more aggressive decarbonization efforts to hit net zero by 2050, according to BNEF estimates.

There’s potential for India to add significant numbers of additional jobs in the solar industry, which already employs more than 300,000 people, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency. Development of the sector will also help to drive down the costs of the nation’s electricity, said Rishabh Jain, senior program lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, a New Delhi-based think tank.

“Our priority should be to reduce our dependency on China,” CEEW’s Jain said. “There is room even for India to raise its ambition for clean energy deployment.”

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government – which aims to have 500 gigawatts of clean energy capacity by 2030, roughly double the current total — has had some, albeit limited, impact with policies aimed at stimulating the domestic solar sector. A total of 22 gigawatts of new renewables capacity was added in the first half of 2025, a record volume and 56% more than a year earlier, according to the Central Electricity Authority.

Import duties of 40% on solar modules and 25% on solar cells were imposed in 2022. Project developers must also use modules supplied only by a government-approved list of manufacturers. While India’s module imports totaled about 20 gigawatts in 2024 — 85% of which were from China — the total plunged after the rule was brought back into force last April, following a year of relaxation to ease a module supply crunch.

Module production has grown twelve-fold since early 2021 and solar cell manufacturing capacity more than doubled in the past year, government data shows.

A crucial next task is to ensure India is producing sufficient quantities of solar cells — which would enable local firms to assemble more finished modules and panels. An approved cell supplier list is scheduled to kick in from June 2026, though that deadline could be dependent on the continued rapid expansion of local plants and the ability of domestic producers to lower costs.

For now, China-made modules remain cheaper than domestic products even after a 40% import tax is applied, though costs of India-made equipment fell almost a third last year and are expected to continue to decline as the local industry builds scale.

The US is India’s dominant export market, and was the destination for 97% of module shipments in the first half. India’s manufacturers have had ambitions of rapidly lifting those volumes, and capitalizing on US wariness about China’s dominance of clean technology.

Yet the strategy faces a fresh challenge from President Donald Trump’s trade policies. Trump on Aug. 6 threatened to double tariffs on India to 50% by next week as a result of the nation’s purchases of Russian oil, and when combined with an existing 14% levy on solar imports it will mean manufacturers face more punitive terms than some rivals.

US solar companies too, are raising objections to the prospect of increased flows of India-made products. The Alliance for American Solar Manufacturing and Trade, which includes First Solar, Mission Solar Energy and Qcells, in July filed trade petitions against India, Indonesia and Laos, alleging illegal practices by largely Chinese-owned companies operating in those countries. The group has called for antidumping duties of 213.96% to be imposed on India.

The US Department of Commerce — which in April set new duties as high as 3,521% on solar imports from four Southeast Asian countries — has launched an investigation. While there is likely to be a short-term negative hit, “we are hopeful that over a period of time these markets will remain open to us,” Premier Energies’ Rustagi said. “India is in a strong position to supply solar panels and other clean tech equipment to the US and other markets.”

An additional barrier for solar firms outside China has been the No. 2 economy’s grip on supply of manufacturing equipment, and particularly the appliances used at vital stages of the production process. That’s creating further risks for Indian producers, with China already showing a willingness to restrict the flows of some specialized appliances or expertise in competitive sectors.

“They're not sharing that right now with the rest of the world,” ReNew’s Vaswani said. “They would like to obviously retain that part of the value within the country.”

Apple Inc.’s main assembly partner Foxconn Technology Group has faced curbs on equipment imports to India, amid a wider drive by authorities in Beijing to curb technology transfers and to prevent the development of rival supply chains overseas, people familiar with the matter said earlier this year. In July, Foxconn asked hundreds of Chinese engineers and technicians to return home from its iPhone factories in India, according to people with knowledge of the details.

Talks this week in New Delhi between Modi and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, along with the Indian leader’s pending visit to China, have raised some expectations for a thawing of restrictions.

India is gradually building up capacity across the solar supply chain, and will continue to add import restrictions and other measures to foster local manufacturing — potentially including domestic manufacturing requirements for solar projects, according to government officials, who requested anonymity to discuss private policy plans.

In February, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman outlined a broader national manufacturing mission with an aim to bolster India’s export competitiveness. While fine details of the policies are still being developed, solar equipment is being considered among potential priorities, some of the officials said. India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

“Every country has to decide their path for energy security and India has clarity on that, it is taking steps to become self-reliant,” Waaree’s Paithankar said in an interview.

Investors too are showing increasing enthusiasm over India’s green prospects. Solar projects attracted a record $14.2 billion of investment in India last year, according to data complied by BNEF. Waaree, Premier Energies and Acme Solar Holdings Ltd. were among firms that led a flurry of clean energy-related initial public offerings in 2024, while Rayzon Solar, Juniper Green Energy and Emmvee have all filed documents to prepare for a new raft of listings.

At Borosil’s plant in Bharuch, Kheruka explains the facility uses mainly equipment from Europe, though crucial glass tempering machinery was imported from China. The company in May confirmed plans to add 600 tons a day of additional capacity.

The producer has pressed India’s government to continue to support the development of local supply chains and insists greater self-sufficiency in the solar sector is an achievable goal.

“We're making satellites — this is nothing, it's not rocket science,” Kheruka said. “China has absolutely nothing that's unique to them.”

You may also like

72 pc Indian employers expect new job creation in H2 2025: Report

BBC Breakfast host Jon Kay unrecognisable in throwback image with famous soap star

Big relief for animal lovers! SC revises order, tells MCD to let off all stray dogs except the aggressive – Here's what unfolded in 11 days

Minneapolis mayoral polls: Candidate Omar Fateh loses key endorsement; Minnesota Democrats revoke support

'I thought I was fine, then husband saw photos I took in the toilet'